The central premise of Robert Macfarlane’s wonderful first book, Mountains of the Mind, is that the mountains we encounter are a strange almalgam of rock, stone, ice and our own imaginations. He suggests that mountains are formed (in some ways) as much by the drift of ideas as by the action of the continents brutally smashing into one another. By way of history he shows how, until the 17th century, Western people experienced mountains as rather ugly, almost a mistake on the part of God. Then Lyell came along and uncovered the deep, deep time of geology, and the mountains became a way to time-travel. And now: majestic, sublime, fearful, they are the places you go when you want to come face to face with your own extinction.

Macfarlane says that the gap between the mountain of one’s imagination, and the real mountain of rock and ice, is often a fatal one.

I think it’s possible to apply this theory to virtually every experience in life. We are always dancing this dance between what is real and what we have constructed in our imaginations. And what is real is also mediated through culture and performance, so as to make us feel that we have closed the gap, that we understand. But nobody understands a mountain. One cannot even see a mountain without the superimposition of one’s memory, ideas, science, visions and dreams layered over it like a transfer.

So it is, I think, with every event of nature, including people. We don’t see each other as we are. We cannot. We cannot see things as they are – there is no such thing-as-it-is. Not for us humans, no. Because we cannot experience anything without first filtering it through our minds, washing it out with soap and water, spinning it into something other. I think that is fundamentally what it is to be human: to impose a narrative upon the world. We turn everything into a story about us.

This gap between things as they really are and things as we believe them to be may be a dangerous one for mountaineers, but for writers, it is the source of something important. Macfarlane himself has written a book that makes use of this very gap, and he has created something that is not a history, nor a memoir, nor a scientific treatise, nor a fiction, but something in between all those things. Something interstitial. Something numinous, and wise, and transporting.

For speculative writers, this gap between what a thing is believed to be, and its true thing-ness, gives rise to what I would call the Weird. The interstitial, the liminal, the estranging, the unfamiliar, defamiliarising, jarring, disturbing… It’s not fantasy or science fiction – it’s not just ‘another world’. It is this world, at an angle. In one sense, it is absolutely as real as reality. But we agree that reality is not really real, not in the sense of things being as they are, and the Weird comes out of that gap between reality and story about reality, and makes the gap visible.

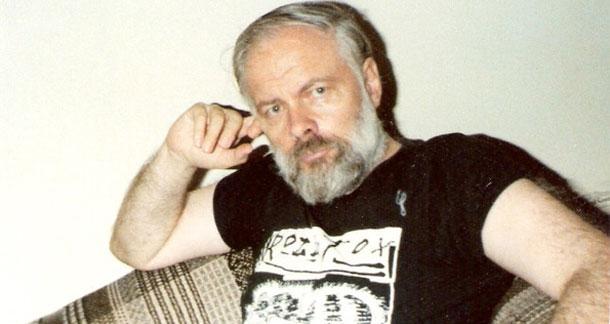

Philip K Dick once said that his project was to explore the question, ‘What is reality?’ In doing so, he had to go very deep into the gaps between things, so much so that he could even be called a fantasist or a madman. For me, this sums up the Weird. It is not an aesthetic, not a genre, even, but a willingness to dwell, imaginatively, in the uncertain gap between fiction and reality.